My volunteering experience in Okhaldhunga, a rural area nestled among hills and mountains in eastern Nepal

– Filippo Zaffaroni

I’m sweaty and tired but also incredibly excited. I’ve just stepped out of a brightly decorated off-road vehicle after covering roughly 200 kilometers of mountain switchbacks, jungle river bridges, and roads so rough that calling them uneven would be an understatement. Along with two companions — a Japanese guy and another Italian — I’ve spent almost ten hours on this ride, alternating between feeling cold, hot, and uncomfortable and making stops along the way for food that was delicious but far too spicy for me (I would eventually get somewhat used to this small inconvenience, but only partially). Now, we’re standing in front of a beautiful building surrounded by a carefully maintained courtyard accessible through a large metal gate. Around us is a tiny rural community made up of a few ramshackle houses connected by sparse dirt roads. We’ve finally arrived at the NaraTika Community Learning Center, where we’ll be staying for a couple of weeks. This is one of the small farming settlements scattered across the Okhaldhunga district, a rural low-mountain region east of Kathmandu, Nepal.

But why am I here? How did I end up in this place? And most importantly, what did I do during the days I spent in this remote corner of the world? Let’s start from the beginning.

How it all began

A few months ago, during my university semester, I was thinking about how to make the most of one of the last summers I’d have as a student by doing something different from the typical vacation in Southern Italy. I wanted to travel, go far, and do something meaningful — not just for myself but also, if possible, for others. I wanted to immerse myself in a different reality, experiencing a new culture that could offer me more than the usual summer nights spent in clubs. For a couple of years, I had been saving money for a trip like that. That’s when I decided to visit the

Website of Lunaria, an organization I had worked with during high school for volunteering and cultural exchange initiatives in Northern Europe. While browsing the site, one project in Nepal caught my eye. It focused on permaculture — a sustainable agriculture model inspired by natural systems, which provides specific benefits, particularly in farming areas facing challenges and limited access to technology. The work camp was organized by Volunteer Initiative Nepal (VIN), an association founded in 2005 and based in Kathmandu, which partners with Lunaria. VIN organizes and promotes various initiatives across several regions in Nepal (the hilly outskirts of Kathmandu, and the districts of Okhaldhunga and Nuwakot) aimed at improving the health and socioeconomic conditions of marginalized communities, with a special focus on women and children. This particular project, Permaculture – Sustainable Food Production, aimed to introduce a more efficient and replicable agricultural model to the community surrounding the city of Okhaldhunga. The area has a subtropical climate, and its population is severely affected by the impacts of climate change, including increasingly extreme rainfall during the monsoon season and harsher, prolonged droughts during the dry season. Reading through all the details, I immediately realized this was the experience I had been looking for. As an agronomist currently enrolled in a master’s program focused on food production and the agri-food system, I saw a perfect match. Not only could I gain knowledge beneficial to my professional development, but I might also contribute something extra to the cause thanks to my prior expertise.

The beginning of the adventure

Convinced of my choice, I got to work on all the necessary preparations, and a few months later, as if it were nothing, I found myself landing in Kathmandu, full of curiosity and eager to explore. Waiting for me at the airport was Nabaraj, an incredibly kind and helpful guy who would later become my friend. He and his wife manage the hostel at VIN’s headquarters, where all volunteers are hosted for a few days before heading to their project locations. They handle the reception, room preparation, and meals — three per day, usually consisting of daal (lentil soup), baht (rice), and a variety of fresh and cooked vegetables. Everything is always delicious. Nabaraj helps me into the car, and I am immediately confused: as soon as I get in, I find the steering wheel right in front of me and the pedals at my feet. That’s when I realized Nepal drives on the left — a detail I was unaware of. We laugh it off, switch seats, and set off for the hostel while I gaze out of the window like a child in an amusement park. The hostel is a small building painted blue and white, located in the lively Khusibu neighborhood of bustling Kathmandu. Through a gate — always left open during the day — you enter a small brick-red paved courtyard, adorned with neatly maintained flowerbeds and the classic colourful Buddhist prayer flags, a ubiquitous feature in Nepal. Welcoming anyone who steps into the facility is the VIN sign.

The hostel and headquarters of VIN, in the heart of Kathmandu

On the ground floor, there’s a kitchen and a multipurpose room used as a dining area or, depending on the occasion, a space for meetings, lessons, and orientation sessions for volunteers. There’s also a bathroom, the room where Nabaraj and his family sleep, and some showers located in a slightly hidden area of the courtyard behind the building, which I never used. On the first floor are the volunteer rooms, furnished with bunk beds, and another bathroom. The second floor houses the association’s offices. All around, you can constantly hear the lively hum of the neighborhood: people chatting, vehicles passing by, tools at work, animals, folks playing sports on makeshift fields, and children dancing and rehearsing choreographies in the school courtyard nearby. I love it. As soon as I enter the room, I pick a bed and lie down, trying to recover a few hours of sleep lost during the overnight journey. When I wake up, I meet Yutaro and Koki, two Japanese guys with whom I’ll share most of my time during my three-day stay in Kathmandu. The city, the nation’s capital and a symbol of Nepal encapsulates its rich historical and cultural heritage.

Kathmandu, Nepal, in a city

Nepal is a poor and underdeveloped country whose society has historically been divided into castes (although in modern times, especially in cities, this categorization is losing its importance), and every aspect of life, from food and clothing to even professional occupations, is culturally classified. In this context, the knowledge of one’s own culture and the sense of belonging are fundamental aspects of the population’s life, which daily adhere to codes of behavior, dress, language, rituals, conduct norms, and belief systems. Nepal is home to a vast array of different cultures, languages, and traditions. The main religion is Hinduism, practiced by about 80% of the population, followed by Buddhism (about 10%). These religions are interpreted and practiced differently depending on various factors, including region and ethnicity, which are often correlated. Speaking of ethnicities, there are over 120, with some of the most well-known and numerous being Chhetri (the largest, about 16% of the population), Brahmin (hill), Magar, and Tharu. Nepal also has a long political history: nestled between two powers like India and China, from which it has experienced significant economic and political influences, it was a monarchy for most of its history before becoming a federal democratic republic in 2008, following the Maoist revolution, which lasted about 10 years.

This great mix of history and culture is perceptible in every corner of the capital. Even for the least sensitive traveler, it’s easy to realize that what you’re breathing in is not just smog (the air in the city can sometimes be quite heavy) but also a surprising blend of customs and traditions that coexist in apparent harmony. Kathmandu is, for me and my two new friends, the perfect introduction to Nepal, a plunge into something completely different from what we were used to, a jarring but personally, pleasant and stimulating experience. During these days, we mostly walk around the city or use InDrive (the Nepalese version of Uber), except for one trip where we experience the unique adventure of public transportation: some vehicles resemble small vans, with an attendant standing by the entrance door, which is often missing, shouting what are presumably the stops and fares. Of course, for this occasion, we are assisted by Nabaraj, who explains to the driver where we want to go, collects 20 rupees per person (about 0.15 euros) to hand over, and pushes us onto the overcrowded van, where we are seated practically on the laps of some girls who don’t even flinch.

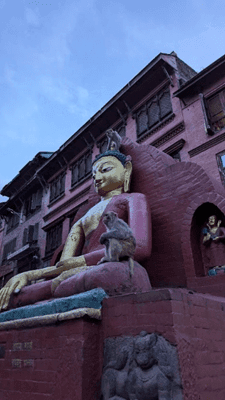

Devotees engaged in religious practices in front of a representation of the god Shiva.

In Kathmandu, we visit the main Buddhist temples, always filled with a mystical and suggestive atmosphere: Swayambhunath, the “Monkey Temple,” built on top of a hill covered with dense vegetation in the heart of the city, and home to hundreds of monkeys that live in very close contact with tourists and locals; Boudha Stupa, surrounded by a round square where shops selling handicrafts and small restaurants with panoramic terraces overlooking the temple dome are located. We walk through Thamel, the ultimate tourist district, well-maintained, full of shops and restaurants, as well as the main hub of the city’s nightlife, and wander through Durbar Square, home to important government buildings and Hindu places of worship, in the centre of a complex network of chaotic and crowded alleys where one often encounters people burning incense and various aromas in front of representations of Shiva and other Hindu deities. We quickly learn (out of necessity) to cross the street by jumping into traffic, talking and interacting with as many people as possible, and trying Nepali food: among other dishes, sashiko, thukpa, and my favorite, momo, Tibetan-inspired dumplings filled with various ingredients.

Swayambhunath, the “Monkey Temple”

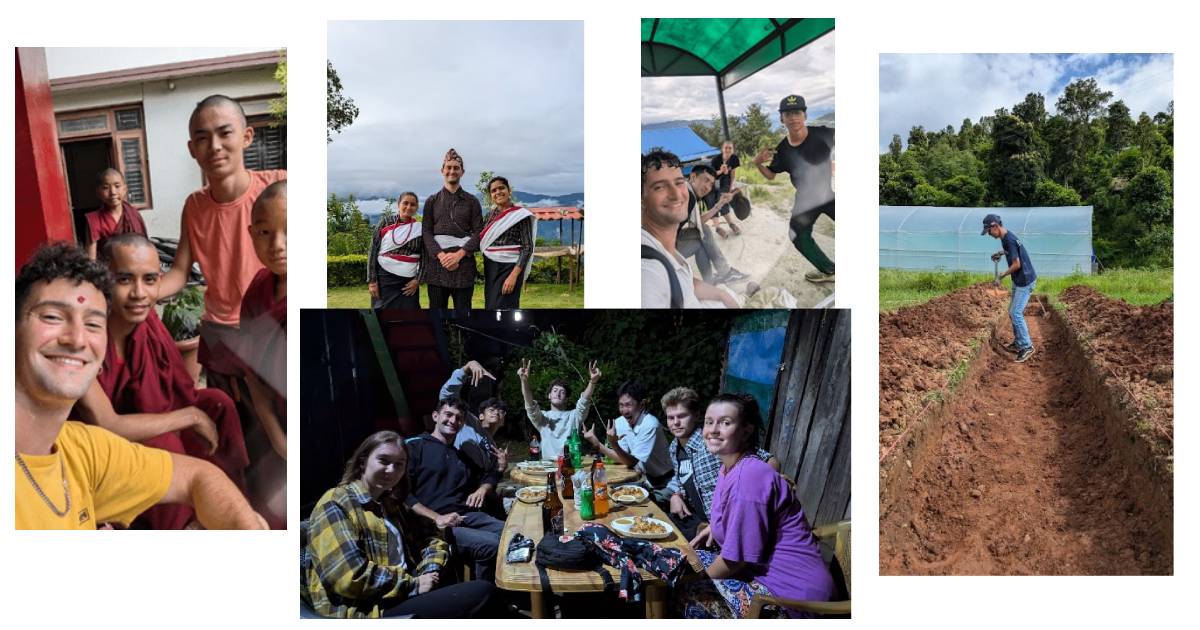

Human interactions are the most representative experience of Kathmandu. From bargaining with shopkeepers and street vendors to the game I started playing with Yutaro: asking the person I’m speaking with, after just a few seconds of conversation, to guess my nationality to see if I can hide my Italian accent (they always guess it on the first try). Every conversation, and every purchase, is an opportunity to try something new. One day, while wandering through the alleys in the centre, as the others buy some herbal teas in a shop, I noticed the presence of a Buddhist monastery in a small square nearby. Immersed in the chaos of the city, the building loses some of the mystical charm one might expect from such a place, but it still sparks curiosity, so I approach and timidly ask if I can enter to take a look. Inside, the atmosphere is calm, as if there were a sort of barrier between here and the outside, just a few meters away. There’s a counter near what seems like an altar, filled with offerings of all kinds. What surprises me the most, however, is seeing a young monk doing the “siuuu,” the famous celebration of Cristiano Ronaldo. Being a huge fan of the footballer myself, it comes naturally to imitate him, and this creates a bridge that allows me to exchange a few words with the young monks present in the monastery, something I was a bit too shy to do just moments before. I ask them what they do, and how they live, and we manage to have some truly interesting moments, bringing together two worlds—mine and theirs—that I had thought were light-years apart. The older monk (next to me in the photo) gets excited when he finds out I’m from Milan: he’s an Inter fan and loves Lautaro Martinez. I tell him I’m also a fan, and we exchange numbers so I can send him videos of the latest championship celebration.

The entrance of the monastery and the photo I took with the young monks inside

The impact of the countryside

The days in the capital are so intense that they fly by in no time, and so one morning, at dawn, we leave the chaotic city and finally reach Nishankhe, the tiny village in the Okhaldhunga region where we will carry out our volunteer work. The Kathmandu trio separated, and the off-road journey was tiring, but at least I had the chance to enjoy some stunning landscapes and also the time to study a few useful expressions in Nepali, which I had written down the day before during orientation. The contrast with the metropolis is striking: here, peace and tranquillity reign and the most distinguishable sounds are produced by a few people chatting in the distance and some farm animals, with chickens and buffaloes being the most noticeable. The air is clearer and cooler, and in front of us lies a landscape of lush hills, behind which the Himalayas rise, though, unfortunately, at this time of year, they are almost constantly covered and hidden by clouds. We are introduced to the structure and meet the few other volunteers present: a few French people and Utsav, an 18-year-old boy from Kathmandu, with whom I would form the best friendship of my entire experience in Nepal. After the formal introductions and an explanation of the rules of the centre, we are finally taken by the French volunteers to a place that would become our regular stop for beer and snacks after work: a small bar run by a couple offering drinks and some dishes, such as steamed or fried momo, fries, noodles, and pokhoda, fried vegetable meatballs. The day has been long, it’s time to take a shower and go to sleep, as tomorrow will be our first day of work.

The view from the highest terrace of the NaraTika Learning Center, the largest building in the entire community

The work in the fields is hard, at least for someone like me, who, although quite athletic, is still a city boy. The tools in the field are rudimentary, and there is no mechanization. The route to the site consists of dirt roads and paths that cross forests and small cultivated plots; it takes about an hour to get there and half an hour more on the way back due to the steep elevation change of about 400 meters. This, of course, if you know the way. And Utsav, who was supposed to guide us, doesn’t know it all that well, so the first few days, both on the way there and back, we have to manage with GPS, landmarks, and supposed shortcuts. We would only find and learn the best route after a few days of adventurous (and tiring, and fun) attempts. In any case, what matters is that we arrive at the field already soaking wet, and only then does the real hard work begin. The first day is the most physically exhausting for me. The more I hoe the ground under the sun, the more I feel that my lung capacity can’t keep up with the movement of my arms. Several times, I feel that the abundant breakfast of rice, lentils, and various vegetables, eaten just a few hours earlier, is about to come back up. The climate is hot and fairly humid, with little wind. When it’s time to stop for an hour for lunch, I also realize that I’ve already finished the two liters of water I had brought, and the rest of the group is not much better off. A providential elderly couple who lives right next to the field offers us some of their water, which they keep in a tank that doesn’t look very reassuring. In Nepal, it’s highly recommended to be very careful with water if you don’t want to spend entire days in the bathroom, but fortunately, Anna, the other Italian volunteer, has a filtering water bottle with her, so we can drink and survive until 3:30 pm, when we finally head toward the base camp. The return trip is not much more pleasant: we get lost several times and run out of water again. I enter what Utsav tells me is a bar (to me, it looks more like a house hidden in the vegetation, with mountains of accumulated stuff inside), and, addressing the boy who was looking at me strangely, I just say: “pani, pani!!” (“water” in Nepali). I get the feeling that the boy almost feels sorry for me (I am in a truly pitiful state), and he quickly hands me a huge bottle of Sprite filled with water, without even charging me for it. We filter it too and can finally make it back home. Shower, ice-cold beer at “the momo place” (that’s what we called it for the following weeks), a good and plentiful dinner cooked by Didi, and it’s off to bed. I am exhausted, my body hurts, and my ears and neck are sunburned. I take a preventive anti-inflammatory and go to bed early. I would sleep almost eleven hours, a rare event for me. My first day might sound like a nightmare from the way I describe it, but it’s not. There were some inconveniences, mostly due to the lack of habit for certain activities and inexperience, but what accompanied me and the other volunteers throughout the day was always a good mood. Despite the fatigue, heat, and thirst, the feeling of positivity and amazement toward everything we were experiencing always prevailed, as it would almost always be until the end of the volunteer program.

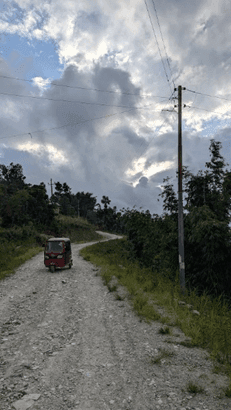

The path that leads from the accommodations to the field where we work, winding through dirt roads and trails surrounded by lush nature.

On the left, the couple who saved us by offering water. On the right, us, tired and sweaty, trying to catch our breath while sitting at a bus stop on our way back from the field

The next day, I woke up unexpectedly fresh and rested. The big surprise of the day is the Himalayas, free from clouds, appearing on the horizon behind the green hills, looking captivating and imposing despite the distance. I climb up to the terrace on the top floor of the building and do some stretching, surrounded by the silence of the hills, with Mount Everest in front of me. It is with this view that my second day of volunteering begins, but more importantly, the process of adaptation that would characterize my entire Nepalese experience, perhaps the aspect I carry with the most pride (and affection). I start carrying four litres of water in my backpack instead of two, applying sunscreen to my face, and wearing a cap with the dirty shirt from the previous day underneath, like a veil, to cover my head from the sun. This would be my style every day in the fields: dirty pants and a sweaty t-shirt used as a turban (all left on the terrace overnight to air out). Every day, I get better at orienting myself between the road and the shortcuts, feel less fatigue, and even come to appreciate it, almost learning to live with the sensation of sweat-soaked clothes on my skin. The blisters on my hands from the first days quickly turn into calluses. All of this is because every day, along with Utsav and the other volunteers, we not only work but also chat, listen to music, dance, and have fun. It is this positive spirit, this desire to learn and challenge myself, and the connection with the other volunteers that brought about a surprising evolution of both my character and my physical endurance in just a few days. I’m happy to be here, and I’m happy to do what I’m doing – that’s what matters. Almost every day, after work, I work out with Utsav in the small room designated in the centre where we stay, something unimaginable to me after the first day.

Our work in the field

The work consists of digging a planting bed where various vegetables will be planted in the future for the surrounding community. The expected result is a trench with a rectangular cross-section, about ten meters long, one meter wide, and approximately 70 centimeters deep. Every day, we are on average four or five volunteers working on the planting bed, and the available tools consist of hoes and shovels. The work is made more complicated by the climate: we are in the monsoon season, and it rains almost every night, making the soil much heavier and more compact, especially in the early hours of work. This means that most of the time during the two weeks of volunteering is spent digging the trench. Once this phase is completed, the planting bed itself must be prepared by filling the dug space with various layers made of different materials with complementary characteristics and functions. The materials used include large branches, smaller branches with both green and dry leaves, manure, compost produced on-site using organic waste materials, and the soil removed earlier to dig the trench.

Various stages in the preparation of a seedbed

The goal is to alternate and combine natural fertilizing and conditioning substances to achieve a resilient and self-regulating soil for planting, capable of sustaining cultivation for years to come. Conditioning substances are, by definition, more recalcitrant materials, meaning they decompose more slowly. These materials improve the structure and overall quality of the soil in the medium to long term, increasing soil microporosity and releasing bioavailable nutrients to the crops gradually. Fertilizing substances, on the other hand, decompose more rapidly, making inorganic molecules available for absorption by the roots in a shorter period. In our case, the materials primarily acting as conditioning agents are large, highly lignified branches, which decompose over a prolonged period, while manure and compost, placed in progressively more superficial layers, serve mainly as fertilizers. Greener branches and leaves, which have a dual function, are also arranged in alternating layers with the previously dug soil. The latter must be well crumbled (with as few clumps as possible) to promote the formation of structure (a well-structured soil, unlike overly compacted soil, has many microporosities, which are essential as they form the spaces where water and oxygen for the plant roots are retained). The particular type of compost used, vermicompost, is produced next to the work site, in special covered vats: it is compost generated by the digestion of organic waste by earthworms, which turns it into a sustainable source of nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium for plants.

Evening snack together at the ‘Momo Place’

The environment we are immersed in

The daily work activity is the reason we are here and represents our contribution to the noble cause carried out by VIN. However, what truly enriches the experience is certainly the setting in which the activity takes place, providing new experiences and stimuli for all the senses every day. From small things, like when an elderly lady who lives near the fields brings us a snack of homemade liquid yoghurt and roasted corn on the cob, to slightly more substantial adventures, like when we get lost in the forest looking for the famous shortcuts and end up almost climbing the hills, holding onto shrubs and tall grasses while singing Celine Dion songs. Seeing locals climb trees to cut branches (the ones for the seedbed) with machetes, witnessing a family slaughter a buffalo on the path leading to the fields, taking part in a Pasni, the event that celebrates the first time a few-month-old baby eats rice, wearing traditional local clothes — these are all small experiences that happen almost unexpectedly every day and make my stay in Okhaldhunga a continuous, unpredictable surprise.

On the left, Didi, and Sunita (another local volunteer) are dressed in traditional clothes. On the right, is the slaughter of a buffalo on the path to the field.

The slight concern felt when we are in the fields and a few raindrops begin to fall is a sensation that now, as I write, I think of with a certain nostalgia, just as the relief when we are on our way back, tired and sweaty, and receive an unexpected ride in the back of a pick-up truck from a man who, the previous weekend, had taken us to Pattale (another incredible adventure, but that’s another story).

Everyday breakfast, lunch, and dinner are prepared by Didi, a sweet young woman who takes care of various tasks at NaraTika, including cooking. For lunch, we need to give her the lunchbox in the morning, which she fills to the brim with noodles, stews, or soups, often accompanied by the famous roti, while the other two meals are served at the kitchen table, where we help ourselves from containers filled with an abundant amount of different dishes. Didi’s food is not very varied but always extremely flavorful: in addition to the base of white rice and lentil soup, which is always present, there are often vegetables and potatoes cooked in different ways, usually sautéed with various spices (my favorite) or fried. The only fresh vegetable is always a type of huge cucumber, cut into rounds. I’m not a big fan of cucumbers, but I eat them because I know they’re good for me. Sometimes, among the side dishes with rice and lentils, there is also chicken, which could be the subject of a discussion. The taste is always exceptional, rich, and spicy, but the problem, at least for me and the other non-Nepali volunteers, is the way it is cut: we always find pieces with more crushed bones than meat, which are almost impossible to clean. Every time, we look in amazement at Utsav and the other locals who eat it without any problem. Dinner, in particular, is a pleasant moment of sharing, during which we chat with local volunteers who perform different tasks and therefore don’t spend the rest of the day with us. It is during dinner and in the moments after, when we relax on the living room couches, that we share stories about the day just passed and our lives, socialize, joke, get to know each other, and show photos and videos to others. Even the most trivial topics, the seemingly most insignificant details, during these moments, represent an interesting opportunity to learn something about human nature seen through the filters of other cultures and different life models, which is always the most beautiful and interesting aspect of traveling. I learned that in Nepal, some people believe that whistling in the house attracts spirits and should therefore be avoided: I whistle all the time, especially when I’m lost in thought and a good mood, and throughout my stay at NaraTika, I am always scolded by Sunita, a local volunteer. Every time I apologize, but the next day we are back at it again, I can’t help it: I’m aware of the respect due to others’ beliefs, especially when they touch on something so minimally impactful in my life, but my distance from the idea of spirits, and especially from the belief that they are attracted by my whistling, makes it hard for me to pay attention to the issue. This case is part of a series of issues that provide interesting reflections on the fact that people with the same values, feelings, and passions can have beliefs, habits, and customs that seem strange, even absurd, in the eyes of someone with a different cultural background. What I’ve come to realize more deeply during every trip I’ve made, and again during my incredible experience in Nepal, is that many times it’s what immediately appears on the outside, the box, that surprises and strikes, sometimes creating cultural shocks and the resulting difficulties in sharing, often leading to separation and division among people. This external box, however, is merely a means through which very similar values and feelings are expressed, and by delving into and understanding its content, one realizes that people who seem very different and almost incompatible can have a lot in common. Reflecting on this aspect, in my opinion, helps to understand people in a deeper and more real way, determining who we like and who we don’t more based on content than on the container, gradually setting aside beliefs and preconceptions that have always been part of our natural way of interacting with others. During the evenings spent with the other volunteers, these cultural distances shrink thanks to moments of sharing, in which play, spontaneity, and not taking oneself too seriously play a fundamental role. Language is one of the most effective tools to get closer to others. Learning words and expressions in the language of those around us and then using them in conversations, or even just pronouncing them in casual moments without any particular purpose, joking with each other about pronunciation or the difficulty and strangeness of some sounds, all while maintaining a cheerful and relaxed atmosphere: these actions create small bridges between people, connections that have an impact in the establishment of complicity and empathy.

Lunch break on the way back to Kathmandu

During a meal, Sunita asks me if I already have a Nepali name. Surprised and a bit puzzled by the question, I answer no, to which a very quick discussion follows, culminating in Utsav’s suggestion: my Nepali name will be Mundre. Mundre means earring, exactly the kind of ring earring I wear, and precisely on one ear, as I wear it. It is also a common nickname given to those who wear their earring that way, but given the circumstances, it takes on a special meaning for me. I love it and quickly become attached to it, immediately feeling that it somehow perfectly represents the connection between me and everything around me, the experience I’m having, and the people I’m meeting. I become Mundre. Mundre is the Nepali version of Filippo, the version of me that is there, living the moment to the fullest. There is a tradition for the volunteers of Okhaldhunga to get a tattoo to remember the experience once they return to Kathmandu at the end of their volunteer service, before heading home. I don’t return immediately; I plan to take a little over a week to solo travel the country, returning just in time for university to resume. But this doesn’t change much because, no matter what I would have done afterwards, it would still be encapsulated in my tattoo, which represents not just a word, but a much deeper concept. So yes, now I have my Nepali name on my calf, etched there forever to remind me of an unforgettable experience.

Member of

Member of